Deep in the rainforests of Indonesia, a group of miners is betting there’s still billions to be made from the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel.

Global mining giants have largely retreated from coal under pressure from Western investors and governments, but consumption is climbing to new highs. Roza Permana Putra, who oversees the PT Triaryani mine in remote South Sumatra, is among those hoping to capitalize on this gap between green promises and real-world progress.

“Coal is a black sheep,” said Putra, the mine’s local director, taking a drag of his cigarette while motioning towards excavators lifting smoldering piles of coal onto trucks. “This is my baby.”

The 59-year-old first arrived a decade ago when the site was pristine jungle. Since then, rows of trees have been felled and the earth split open for excavation. Singapore-listed Geo Energy Resources Ltd., which bought the mine in 2023, is cranking up coal production. Including its initial purchase and ongoing infrastructure investments, the company is spending a total of around $500 million on Triaryani. The wager is simple: that demand will linger far longer than experts predict.

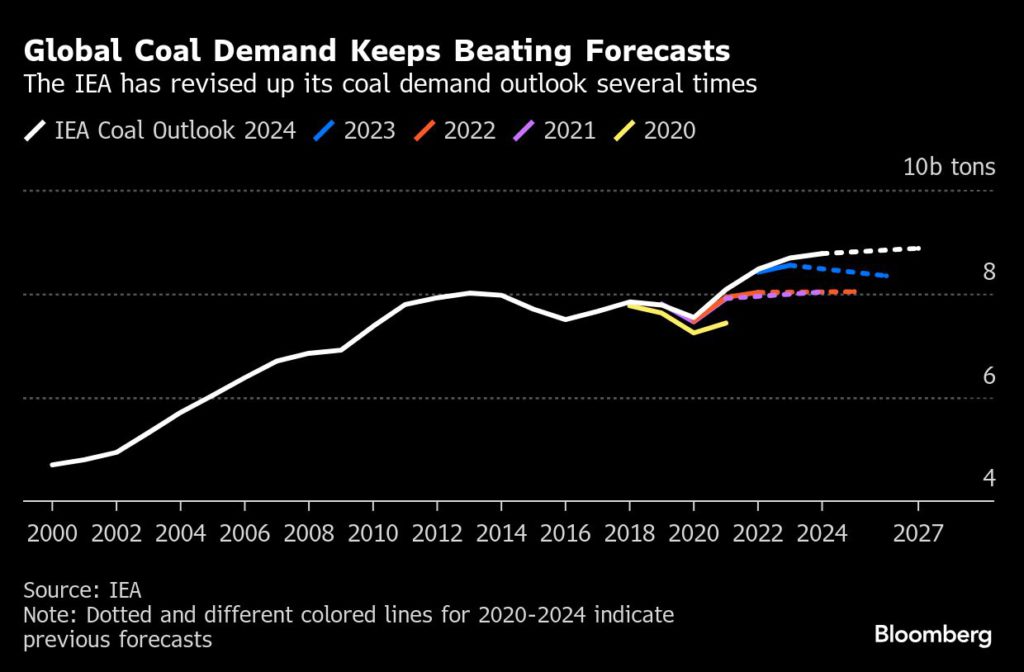

So far, the bet looks solid. Although much of the developed world is reducing coal mining and shifting to renewables, global demand hasn’t yet peaked as expected by researchers including the International Energy Agency — a reality reflected in the shifting rhetoric of political leaders.

In the US, once a global climate leader, President Donald Trump has axed clean energy incentives and extolled the virtues of “beautiful, clean coal.” In Indonesia, recent governments have tacitly allowed industries to burn more coal to power a growing population. Nations aren’t on track to cut emissions as pledged under the Paris Agreement — an inconvenient truth that negotiators will confront at the upcoming COP30 climate summit in Brazil.

Geo Energy isn’t a wildcatter in the traditional sense, since it’s developing sites already proven to have coal deposits. However, it’s one of dozens of opportunistic players in Asia acquiring underdeveloped or mothballed mines from retreating majors. They are the new face of the coal industry — nimble and less constrained by ESG pressures. Many of these mavericks are looking to mimic the success of PT Bayan Resources’ founder, Low Tuck Kwong, who became one of Indonesia’s richest men by investing in coal mining in the 1990s.

Charles Antonny Melati, Putra’s boss and Geo Energy’s co-founder and chief executive officer, said his company was perfectly positioned to take advantage of the untapped deposits left to niche players speculating on coal’s long goodbye.

“Big players want to exit. But small ones cannot enter, because the mines involved are very big and capital intensive,” said Melati, who co-founded Geo Energy in 2008. “For us in the middle, it’s an opportunity.”

Originally a mining service supplying trucks and heavy equipment, Geo Energy acquired an East Kalimantan coal mine in 2011. That and several more deals transformed the company into a mine owner and operator. Triaryani, though, is by far its biggest venture yet.

Workers are building new infrastructure aimed at boosting annual production from about 3 million tons today to 25 million over the next few years. The expansion project is expected to turn it into a top Indonesian coal miner, well placed to reap a windfall if demand holds up as global supply starts to shrink.

Or it could bankrupt them.

The mine’s fate is critically tied to China. Indonesia’s coal production hit an all-time high last year but output is poised to fall in 2025, due in part to weaker demand from its top customer. A mild winter, high domestic production, brimming stockpiles and large gains in wind and solar mean the country doesn’t need to import as much this year.

So far, most expect the decline to be limited. China still relies on coal for more than half its power needs and continues to install new coal plants. The real threat, however, is if it continues to expand its own output, reducing its requirement for overseas supplies.

“Our base case is that China is in structural decline,” said Anthony Knutson, the global head of thermal coal markets research at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie. “As they close that market, does that squeeze out Indonesian imports?”

Back at the Triaryani mine, Putra pointed to a man in the back of a truck, pulling a tarp across a pile of coal to keep it from spilling during the long trip to a barge — and eventually, the open sea. The shipment, he explained, was most likely bound for China, which takes the lion’s share of its exports. But the company is trying to diversify, he said. “We try to open other options.”

Yet even with strong demand from other countries like India, the global market has been volatile. Coal miners enjoyed their most profitable years ever following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but an ensuing slowdown prompted prices to plunge over 70% from their peak. The slump caught out some miners in Australia, where several mothballed mines were restarted only to be shut down this year.

Adding to such risks is the higher cost of extracting coal. Indonesia’s most accessible coal reserves have long been exhausted, leaving remote, costlier deposits buried in the mountainous jungle regions of Kalimantan and South Sumatra. Triaryani is about three hours away by car from the nearest major town, Lubuklinggau. Tapping the deposits requires huge investments in infrastructure like roads and jetties, as well as the local know-how of veterans like Putra.

Putra has been working with local communities and contractors to clear forests and thousands of tons of dirt to level the ground — work that’s vital to connect the mine to an export market.

“The coal business is a logistics business. Without efficient roads, you’re just burning money,” said Putra.

Geo Energy declined to give a profit outlook on the mine, but the greater scale could help lift the mine’s annual net profit to well over $200 million from the roughly $25 million expected this year, according to Bloomberg calculations based on recent sales data. This could deliver enormous paydays to its executives and shareholders. If demand falters, though, the company could be left with stranded assets.

Other miners see the tightening regulations and investor demands as too risky to ignore. Once-major players in the industry like Anglo American Plc and Rio Tinto Group have been phasing out thermal coal-related projects and selling assets. Glencore Plc, whose thermal coal business has made it an outlier in recent years, has also said it will not invest in new mines, though that’s in part because limiting global supply will help profitability.

Even in the US, where Trump champions coal, the sector is losing ground to cheap gas and fast-growing renewables. The amount of production capacity added worldwide last year dropped to the lowest level in a decade.

“We appear to be witnessing the final wave of global coal investment,” said Tonmit Talukdar, an analyst at Rystad Energy. “While many countries are scaling back coal production, Indonesia is projected to maintain steady output growth. The window for export-led coal expansion is narrowing.”

Researchers at the IEA and global consultancies have all been raising their forecasts for coal demand. McKinsey & Company, in a report published last month, forecast demand to rise 1% through the coming decade, a reversal from a scenario last year that saw a 40% decline over the same period. Wood Mackenzie predicts coal demand to peak in 2026, but also sees it increasingly likely that consumption will continue to rise through 2030.

Herein lies the industry’s dilemma: Investing millions of dollars into an energy source that governments around the world are actively trying to quit is a tough proposition. But as few players invest in production, a future supply shortage could trigger a significant price surge.

Indonesian miners aren’t the only ones in Asia betting on the chances of an energy crunch creating a windfall. Even in Pakistan and the Philippines, small companies are buying coal mines.

“The ageing of existing thermal coal assets combined with underinvestment in new projects suggests a potential supply shortfall and attractive pricing outlook for the industry,” said Rob Bishop, CEO of Australia’s New Hope Corp., which is expanding thermal coal production.

Indonesia’s pragmatic “have coal, will use it” approach, combined with the energy needs of the domestic market, has made the country a particularly appealing place to keep mining. Back in 2022, the government signed a landmark climate finance deal that promised to accelerate the phase-out of coal and the building of clean power. But that plan — the Just Energy Transition Partnership, later deployed in other middle-income nations — has since made little progress. Officials raised their target for mining output this year, despite production massively overshooting the target in 2024.

“If I’m a coal entrepreneur, Indonesia’s really the place I can go to invest,” said Carlos Fernández Alvarez, coal analyst at the International Energy Agency. “Even if exports fall, domestic demand gives producers another outlet.”

The industry remains crucial to Indonesia’s $1.4 trillion economy, Southeast Asia’s largest. Coal mining alone accounted for about 2.4% of GDP in 2021, according to the IEA.

Some see this dependence as a weakness. “A large part of the economy is tied to a few firms in an increasingly volatile coal sector,” said Hazel Ilango, coal transition lead at the Energy Shift Institute. “This creates a systemic risk that cannot be ignored.”

It could certainly challenge Jakarta’s green-supply-chain ambitions. Electricity generation has ballooned 60% in the last decade, partly due to the huge fleet of captive power plants built to power its nickel smelting industry.

Putra says the project is a way for ordinary Indonesians to keep the lights on without breaking the bank.

“Let’s not sacrifice the lowest cost energy just to chase a dream,” he said, leading the way through the canteen. He then sat down with his subordinates to discuss site progress, their plates filled with deep-fried fish and spicy sambal. “Our people need to live first.”

(By Eddie Spence and Stephen Stapczynski)